Cramming things together may be efficient if you want to package sardines, but living in a high density urban environment is showing to be definitely hazardous to your health of late.

At the time of this writing, the spreading virus has claimed 6,000 lives in the United States and the testing shows the highest concentration of infection in New York City and New Jersey. This metropolitan area of 4-6 million in fact is registering 30% of all cases testing positive in the 50 states. How is this possible?

The way most viruses infect is through contact -- human contact through the air, by touch, from surfaces. Physicians have prescribed how to mitigate contracting the virus through ‘social distancing’ and a variety of other safety measures. As the Covid-19 pandemic spread throughout Europe and the United States, several questions about culture were first raised. We heard about how males were twice as susceptible, and the infirm with previous high-risk conditions. Like others, I wondered about how illness is linked to culture, to smoking and eating habits, to age, exercise, pollution, to underlying disease.

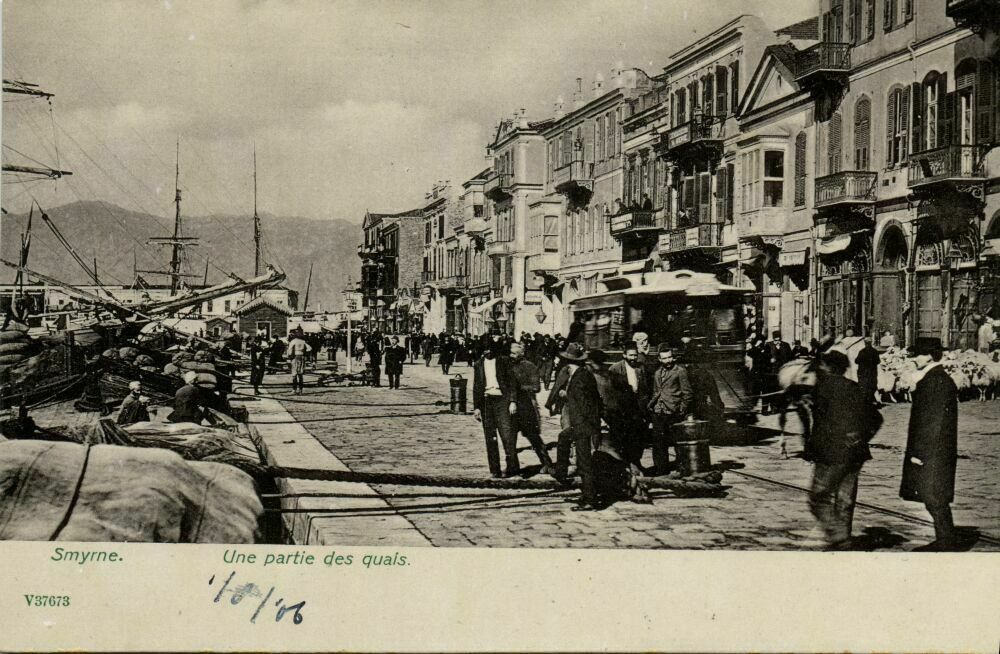

My mother was from Greece and we lived in Turkey through high school. (food and merchant bazaar at right) We had an apartment in a 13-story concrete condo style building on a busy thoroughfare in Izmir Turkey. The windows were left open all day and one could smell the bakery down the road, the vendors selling their wares, the horse and buggies, and the smell of low-quality diesel that would hang in the air after a roaring truck came by. We had no air conditioning for many years. Dust and residue of the city and odors blew through the house. We also heard the Imam praying 5 times a day, bells ringing, cars on their horns, the clip clop of horses, vendors wailing, ethnic and western music at night, and conversations around the neighborhood. As I child, I was fascinated and had nothing to compare to. Like most Turks and anyone else living there, we were healthy and happy. (Modern pedestrian alley, Karsiyaka Izmir, below left)

No one got sick it seemed. Produce was brought in daily from surrounding farms and meats slaughtered and hung for inspection and purchase. I would go to the bakery and see others squeeze the freshly baked loaves to test for freshness. There were no plastic wraps. We were told not to buy anything from street vendors, although that rule was broken. We pretty much ate everything available, from sour yogurts, to fruity ice cream, sesame bagels, and lemonade poured by vendors into glasses flushed out by a quick rinse to be reused immediately.

We carried foodstuffs daily in string bags, rarely washing them I recall. Drinking water was brought in in large bottles as the tap water was to be used for washing and cleaning only. This was 1962 to ’72. But this lifestyle is very similar to that in most urban areas in the United States and Europe, in fact around the world, through the 1920s and 30s. (below:Izmir waterfront quay, 1906).

The culture of Greece and Turkey, in fact in most southern European countries and those bordering the Mediterranean, involves close face to face communications and much physical contact. People walk arm in arm, kiss on the cheeks before and after meeting each other, etc. The bazaars and outdoors are very busy at certain times during the work week and on the weekends while people are constantly bumping into each other. Society interacts at ‘close quarters’ is the best way to put it. And there is a rather loose attitude towards strictly ‘proper’ hygiene. The inhabitants are quite fortified against flus, viruses, etc. due to, I imagine, a continued lax attitude and so everyone slowly builds up a resistance to infections of any kind. Again, I don’t remember being very ill at all during those 10 glorious years.

Immigrants from Europe brought the same customs to this country over many years, while establishing strong pockets of ethnic communities. Now, we examine the current calamity and ask: how is such widespread infection possible? As of this writing Turkey has 300 deaths out of a population of 83 million. That is a much better statistic than most of Europe right now. Greece has 10.4 million with 60deaths. Still, very, very good.

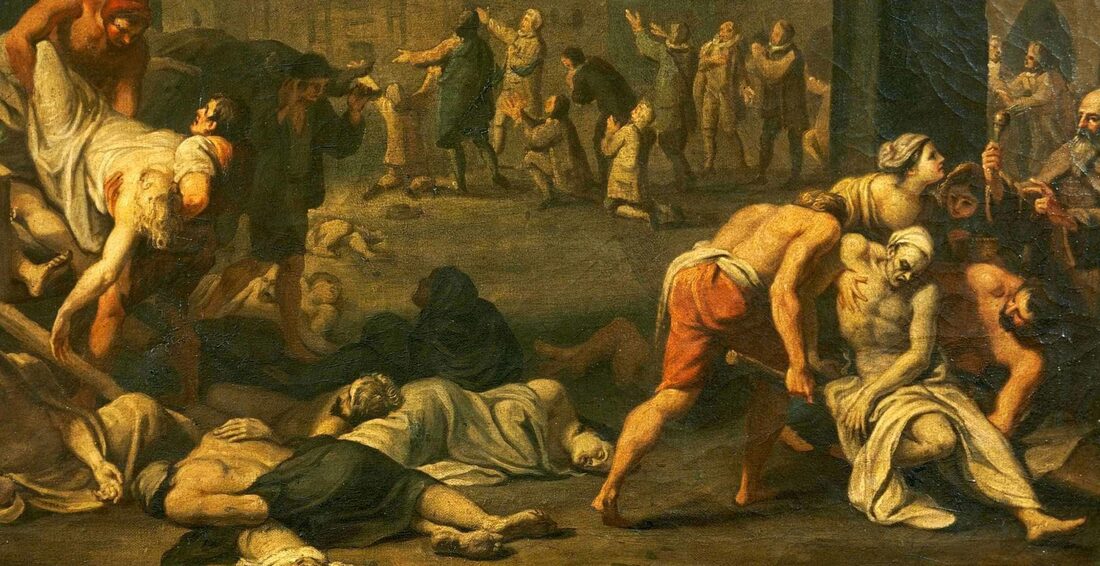

The Black Death of 1347-51 killed 75 to 200 million in Europe and Asia. It is believed the source was eastern Asia, the bubonic plague being carried through the Silk Road and reaching the Crimean ports by 1343. It was likely carried by fleas living on rats aboard Genoese ships and spread through Europe from the Italian peninsula. The term ‘quarantine’ is Latin for 40 days, the length of time these infected merchant ships were forbidden to unload anything or anyone.

Fast forward to 2019-20 and we see something very similar: an Asian source of a virus but this time carried by unwitting(?) travelers throughout the entire planet quickly via airplanes for business and pleasure. Technology brought this virus to the unsuspecting at a rate that may have been beneficial even, as the pandemic seems to affect everyone within a compressed period of time and time will tell if a medical solution is offered in time to quell the catastrophe.

Since a simple handshake or close hug apparently transmits COVID-19, one cannot argue lack of sanitation or poverty as the chief causes of the current pandemic compared to the Black Death which included reasons of unsanitary water, open sewage, etc. The customs I mentioned while living overseas are ethnic ways that are carried here into the United States from migrants of every nationality. Cultural norms are one route of infection. We see now that social distancing is the only way to keep contagion inert.

Quarantine was the chief method of stopping the European plague. Those who were uninfected remained in their homes, while others fled the densely populated cities and lived in smaller quarters in the countryside. A similar flight to safety has been seen and stopped in order to contain the current pandemic. Isolation has been recommended by the medical profession.

Looking at the current numbers for infection and morbidity, it appears that the most densely populated cities are showing the highest rates, at least in the United States. If you look at the continually update chart from Johns Hopkins -- https://www.arcgis.com/apps/opsdashboard/index.html#/bda7594740fd40299423467b48e9ecf6?mod=article_inline you can see that less densely populated areas have smaller rates of infection and death. One can also observe that a larger metro area like LA with reduced density also shows a more lower, manageable rate, which is the main point here.

Obviously, the more dispersed a population is, the less likely a contagion will decimate it. Which brings up the question of cities/ megacities, versus rural and suburban living.

Mulberry Street, New York City ca. 1900, above slides

The hot spot in the country as of this writing is the New York/New Jersey area, posting the most infections and total deaths. The trend is to see dense urban areas experiencing the most damage while rural areas the least. In contrast, the LA metro area is posting less than ¼ of the cases and morbidity per capita than the northeast’s large dense metro areas.

Density of population means closer contact person to person. It means repeated contact with hundreds or thousands of other people sharing sidewalks, streets, cabs, subways, elevators, handling door hardware on multiple venues, toilets, etc. This has architecture and planning implications that must be examined.

Before all the technical ‘innovations’ of the modern world, the ancient world in general was built in mud, brick and stone that limited the heights of buildings. There were thousands of years of 2 to 5 story private and public buildings and the majority of the population lived outside of the city gates in the surrounding farmland. But as work paid more in the city, a migration of the poor and less skilled into tight urban quarters ensued. Plagues and pestilence commonly started in the city central due to poor drainage, open sewers, overcrowding, unpaved streets with animals wandering around, dirty drinking water, etc.

Modern metro areas have overcome nearly all the problems associated with crowded living and working conditions of the pre-industrialized world – as far as advancing sanitation goes.

The influx of Modernist building theory and technology in the ‘40s included the opportunity to build higher with glass, concrete and steel with the consequence of dumping thousands of inhabitants of offices and condos on the streets of cities like Chicago and New York which had not been designed for that volume. While not considered a hazard at the time, this meant hundreds of thousands of people packed on narrow sidewalks, in the subways, stairwells, and pushing into lobbies to board elevators in the high rises.

While this type of construction and urban design drove up prices of real estate, made millionaires out of developers, and hypnotized architects and planners, it had to also be deemed ‘good’ by social scientists who also approved much of what was being built.

One of the preeminent architects of the time, Le Corbusier, introduced his visions of grandeur with a scheme for Paris which would have leveled undesirable areas in order to build large scale apartment and office blocks separated by a busy transit corridor. ‘Ville Radieuse’, the Radiant City (above), has been eerily mirrored in Dubai’s planning (above, slide show). Corbusier also had a solution to pack the less fortunate into large crates, which became a model for huge public works projects in the U.S. like Pruitt Igoe.

In other parts of the world, this Universal Style for housing the masses was repeated endlessly in urban areas, like these modern housing blocks in Zagreb (above, slideshow) and other developing third world housing clusters.

In contrasting the present pandemic, the population of Dubai does not flood narrow streets as in New York or Chicago, nor travels on subways but rather drives everywhere in air-conditioned vehicles. Person to person contact is limited to underground garages to lobbies and elevators to offices and condos while the traditional eateries and shopping areas are several blocks behind the showy boulevards in less dense areas. (above, slideshow: Pruitt Igoe, before it was demolished)

In the early 60s another visionary European architect, Paolo Soleri, offered up high density, self-contained urban environments, sparing the pristine earth below for recreation (and an area to obviously escape the oppressive living areas above!) These ideas were based partly to the reaction of ‘save the planet’ types of the times… but give an architect a pencil and he/she will re-envision the entire manner of living/building and society itself. Frank Lloyd Wright, not to be left out, revealed his ‘Mile High City’ in 1957 which also combined work, house, and entertainment/recreation. (Soleri conception, above, slideshow: Arcology – Architecture and Ecology)

The interiors of modern office skyscrapers are characterized by a ring of individual offices at the perimeter leaving a core of windowless partitions which gave way to the ‘open plan’ -- an innovation borrowed from 50s office culture in Germany. Frank Lloyd Wright was magnanimous in the quality of workspace he afforded the staffs of the Larkin and Johnson Wax office buildings. The open plans had high ceilings, ventilation and light.

The scene (above, slideshow) puts open plan workstations near the window wall but notice the distance between seating is barely 7 feet. A full day of work in this environment will expose anyone to airborne viruses and flus, etc.

The ventilation of modern office buildings needs to be fortified to ward off epidemic, if the work floor area density remains. The typical floor to ceiling is 9 feet and conditioned air should be better filtered with higher rates of fresh air intake. But this will probably not be sufficient to ward off infection through close proximity as the open plan will continue with cubicles packed tightly together and people passing each other in narrow corridors.

(Wright’s Larkin atrium above, slideshow)

There is really no ‘cure’ either, by physical design, to ward off person to person transmission in stadiums for large sports or music/stage events, museums, music theaters and film venues, and places of worship. In times of contagion these structures must be closed to prevent infection through close quarters. But the structure of large metro areas with high rise apartment and offices means that those occupants must travel up and down in tight elevators, lobbies, and then disperse below on the shoulder to shoulder sidewalks and likewise into the subway, bus and tram systems. In the worst-case scenario, these interactions become deadly when the atmosphere is virulent. (Johnson Wax atrium workspace, above, slideshow)

The social scientists and behavioral types have been endorsing ‘community’ in dense living environments as opposed to suburban living for many years now. It is considered better on all counts and from an economical point of view no doubt saves a lot of money on infrastructure. The American subdivision has been vilified for years due to its many faults. Low density housing especially has been reviled by planners constantly. The strip mall, office park, and automobile-centered lifestyle has led to all types of social disorder, they claim.

The interior layouts of regional or suburban shopping malls were restyled, in fact, to mimic the close quarter Old World Euro-style irregular outdoor street shopping experience that Americans so desperately needed to survive and help maintain social order, human contact and supposed sanity. (above, slideshow)

It is obvious that no matter how strongly the argument favors high density living, those in the suburban and rural areas interact the least, touch the fewest contaminated surfaces daily, and are best situated to ride out an epidemic.

Those who are left amidst the highest death tolls in the large metro areas (after this virus is vanquished temporarily presumably through medical treatment) will be thinking about moving away from their hazardous but socially invigorating environments and looking at low density housing as the clear alternative. Or moving to remote areas and simply telecommuting. A new habit takes 21 days to 2 months to form. Working out of one’s home may accelerate and leave thousands of apartments and condos empty in the large metro areas.

There have been many proposed living arrangements that blend healthful living with a working environment integral to the development or located nearby. One can start in Renaissance Italy with the Ideal City, incorporating notions of moral, spiritual and legal qualities of citizenship and go from Enlightenment concepts of science, geometry and harmony to late 19th Century Garden Cities of England to finally the New Urbanism of the last twenty or thirty years. (Renaissance conception, above, slideshow)

In each case the scale and densities of these historic plans are far less than any of the modern congested urban metro areas that have developed to date. Remarkably, few if any high rises are introduced in the newer schemes, most have two or four-story buildings, and the majority show houses on individual plots or arranged to include low density multifamily living.

In 1935 Frank Lloyd Wright proposed Broadacre City (above, slideshow), a democratically organized utopia of individually owned plots of land and houses on a grid connected by motor highways and private helicopters. The remarkable aspect about this idea was the fact that Wright saw this possible due to three factors: the private automobile offering complete independence, interconnectivity with the traditional workplace via the telephone, radio and telegraph, and scientific technical breakthroughs to come. Each house was intended to be self-sufficient with enough arable land attached. The concept was a highly decentralized association of individuals and businesses working together in an ideal environment. He foresaw the American suburban model to come which unfortunately did not allow self-sustenance on small plots with nearly wall to wall construction.

Wright thought that technological advance at the time allowed telecommuting to anywhere and that a hyper dense urban center was unnecessary, ugly and unhealthy even. This is an uncanny parallel to the current temporary workforce displacement from office to home in time of pandemic.

After this terrible disease takes its course and blows through, there will undoubtedly be thousands who will abandon the crowded atmosphere of the dense urban centers and flee to the suburbs or the countryside.

Another model for low density living is England’s planned new town Poundbury (above, slideshow), now in its 27th year. This charming agglomeration of city center surrounded by two and three story private residences and other office and small factory buildings and services intermingled with open squares allows community to flourish without overcrowding. Estimated final population is 6,000 in 2025 with 180 business currently operating and employing all residents. It is carbon neutral with no zoning and totally sustainable.

The question remains: will the outcome of the current pandemic, which so clearly has multiplied in the high-density metro areas, force planners, social scientists, and politicians to concede that the suburbs and automobile centered low density environments are much better insulated against future pandemics? Will we live in the fear of succeeding medical disasters without making any changes? Note that decentralized living means survivability under conventional warfare. Will new designs inspired by Broadacre City or Poundbury be proposed? Or will the fear of pestilence recede with immunization, and pandemic relegated to an unavoidable but acceptable 100-year cycle?

RSS Feed

RSS Feed